Recently, I found myself in a situation where I needed a fastener in thin sheet metal, where I didn't have access to the other side of the material.

That rules out the typical nut. I was going to need a blind nut that could be installed from the outside of the part.

Enter the "Rivet Nut", more commonly called a "Rivnut".

|

| An Autodesk Fusion model of two rivnuts in a piece of sheet metal. |

Available in a variety of materials, they can be installed using a variety of tools that all work on the same principle.

The rivnut is installed into its hole, and a threaded mandrel is drawing by a tool to compress the nut tight against the parent material.

|

| One type of Rivnut tool. There are more than one option, though |

|

| An uncompressed Rivnut threaded onto the mandrel, ready for installation. |

It's similar to a "pop" rivet for those familiar with with those.

It's a pretty quick and easy way to create threads in a part.

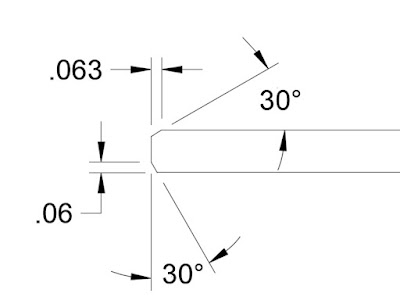

compressed (right) rivnut,

|

| An isometric view of the same view above. |

I've only used aluminum rivnuts, so my experience is limited to those, but here are the drawbacks I've encountered

1) They're easy to cross thread if you're not careful. I've learned to start the screw with my fingers to ensure the threads are running true. Starting the screw with a socket or any kind of power screwdriver is a recipe for trouble (ask me how I know).

2) "Permanent" is a relative term. While reusable, rivnuts always seem to loosen over time. Eventually you end up with the dreaded "spinner". That rivnut that spins inside it's hole and must be carefully drilled out.

Fasteners out of other materials may be a little less prone to the above problems, but not having used them, I'll avoid speaking "out of class".

In conclusion, the rivnut is a fastener that has it's niche. If you made it this far, you may be thinking "That could be really handy!" or "That thing is useless and the universe will be cold and dead before I touch one".

Either way, that's fine! It's just another tool in the tool box!

As a wise 1980s cartoon once stated, "And now you know."

Acknowledgements:

Rivnut models downloaded from McMaster Carr and modified in Autodesk Fusion to create compressed version.

.jpg)