In my last Wednesday, I talked briefly about how rivets are sized. But what about how to choose a rivet for a given application?

In my last Wednesday, I talked briefly about how rivets are sized. But what about how to choose a rivet for a given application?

There are requirements for how to select a solid rivet, and while they may vary slightly from application from application, the FAA publication AC43-13-1B is a good guideline for selecting a solid rivet.

The pages referenced are 4-20 and 4-21, and can be downloaded at this link.

So what do those instructions tell us?

For my example, I'm going say I'm riveting one sheet of .032 thick material to .040 thick material, using a MS20470 "universal", or button head rivet.

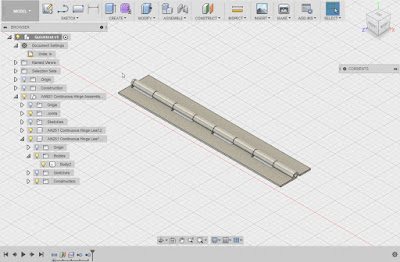

|

| The Sheet Metal Thicknesses shown in red and cyan. The rivet is in gold |

The first step to choosing a rivet is to select a rivet diameter. By referencing the document, you can see that it states that we should use a rivet with a diameter 3 times the thickness of the thickest sheet.

So if the material is .040 thick, then 3 times that thickness is .120, which is close enough to a 1/8th (.125) inch rivet.

So there we go! The diameter is selected! But now, how long of a rivet do we need?

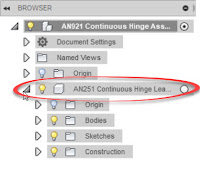

|

| The dimensions of the rivet needed for this application. |

AC43.13-1B states that we should use a rivet that extends 1.5 times its diameter beyond the underside of the material.

Adding .032 and .040 we end up with a total material thickness of 0.072. Extending 1.5 rivet diameters beyond that we get a total length of .2595 inches,

which is close enough to 1/4 (.250) inches.

So this application calls for using a MS20470-4-4 for this particular application.

Now the rivet can be driven with a rivet gun and bucking bar, and the parts can be fastened!

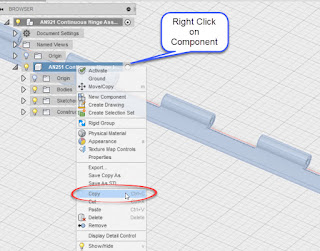

|

| A typical rivet gun and bucking bar set. |

I hope you find this tip helpful!

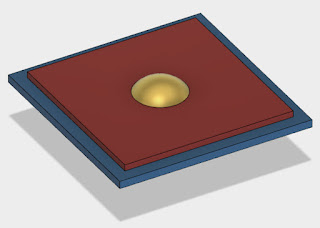

|

| A sample of the approximate dimensions of the set head. |

One final note, the documentation I've used is an "Advisory Circular". If you have engineering documentation, such as a manufacturer drawing or a maintenance manual, do what it says! The manufacturer's data always wins in this case!